At some point during your education, I am sure that you have encountered assignments that mention the use of primary, secondary or tertiary literature. If you are like me and don’t have the greatest memory, you may find yourself having to refresh yourself on the differences between these three types of literature. Therefore, I decided to create this simple guide to help people just looking to get a quick refresher like me, as well as people who are just learning the difference between these types of literature!

1. Primary Literature

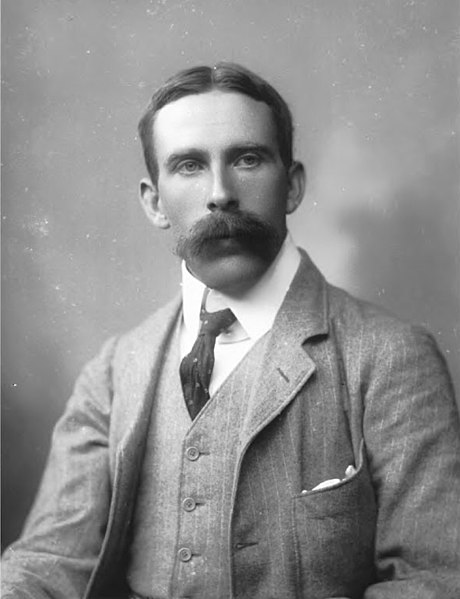

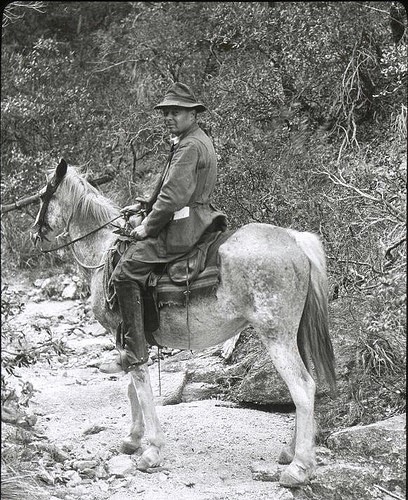

Primary literature contains original ideas and often presents new theory and research at the time of publication. This journal article on the impacts of the invasive plant species, Garlic Mustard, on the understory community of a forest original research and thus an example of primary literature.Another fantastic example would be Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) that contains original ideas and theory on the evolution of species based on his observations during his voyage on the HMS Beagle.

2. Secondary Literature

Secondary literature contains discussions, analyses or interpretations of the ideas and information presented in primary literature. For instance, a meta-analysis on the trait differences between invasive and non-invasive plants is a great example because it examines the research of multiple primary sources. Another example would be a journal article or book discussing and analyzing the ideas of Darwin, such as, Niles Eldredge’s, Darwin: Discovering the Tree of Life (2005).

3. Tertiary Literature

Tertiary literature gathers and summarizes information from numerous primary and secondary sources. Wikipedia pages on invasive species or Charles Darwin would be an example of tertiary literature, as would this article on plants (Yopp et al., 2019) in Encyclopedia Britannica.

This guide was written with reference to:

University of Saskatchewan. (2020, Jan 16). Biology 301: Primary, Secondary & Tertiary Sources. Retrieved from: https://libguides.usask.ca/c.php?g=16486&p=91242